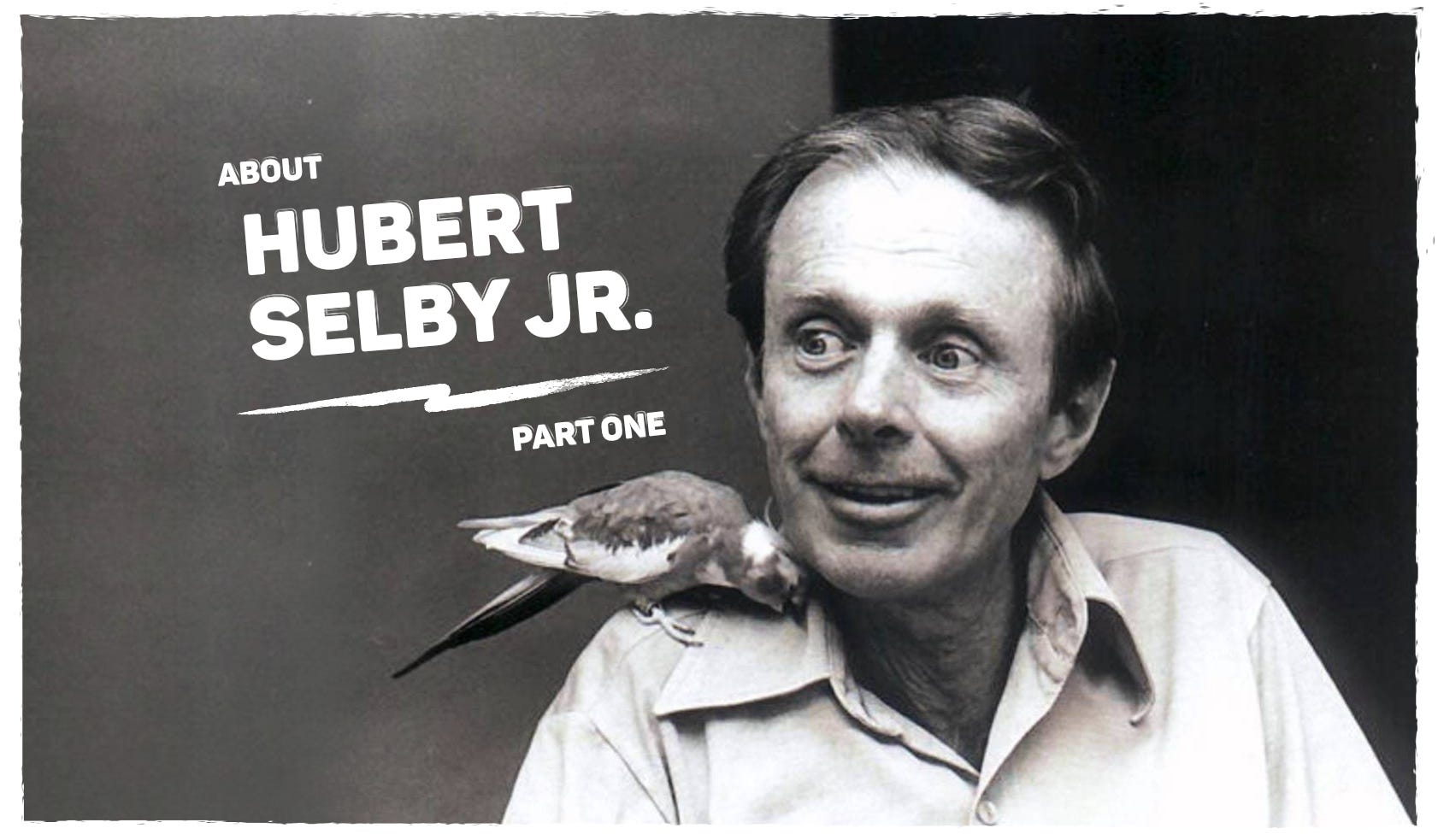

About Hubert Selby Jr. (Part one)

I want to tell you a little about Hubert Selby Jr. and, if you haven’t read him, why you should—or perhaps shouldn’t.

“I started writing because I did not want to die having done nothing with my life.

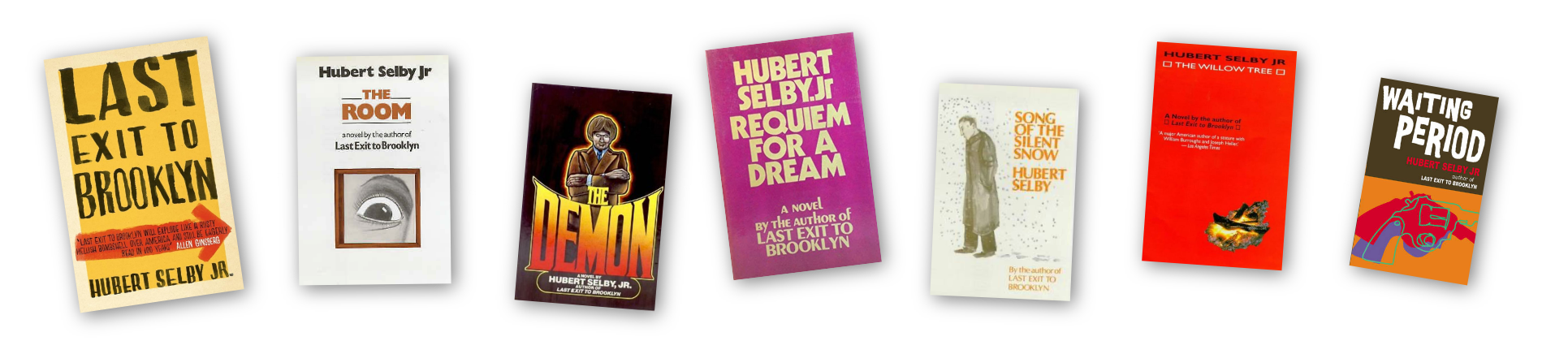

This is Selby’s opening line from his 1994 introduction to Last Exit to Brooklyn, his first novel, published in 1964 (US), and ‘66 (UK), where it was banned for obscenity in ‘67, and later absolved in ‘68.

We/ll begin halfway

Requiem for a Dream, comes smack dab in the middle of Selby’s chronology, and is arguably his best-known work today, due in large part to the Aronofsky film adaptation starring Ellen Burstyn, Jared Leto, Jennifer Connolly and Marlon Wayans. The film version often tops internet lists named such things as The most harrowing movies of all time, and Films too upsetting to watch twice. Given its reputation, it’s unlikely the general filmgoer would go on to pick up the paperback and relive the ordeal anew from the source. And I’m not here to change their minds. Selby’s work is brutal—there’s no getting around it. He’s not a writer you recommend; he’s one you must seek out.

But hey, you’re reading this of your own free will, so I'll assume you are doing precisely that.

Requiem depicts the slow and tortuous unravelling of its main characters’ dreams, along with the disintegration of their health, sanity and freedom. For most, where the book begins would be rock-bottom. Harry1 Goldfarb is a heroin addict who’s taken to routinely pawning his mother’s TV so he and best friend Tyrone can afford a fix. But they’re no longer satisfied scrounging around to feed their habit. Selling, they decide, is where it's really at, and so the duo hatch a plan to buy, cut and offload dope, with an eye to make some real money:

All we gotta do is cool it with the shit, you know, just a taste once in a while but no heavy shit - Right on baby - just enough to stay straight an we/d have a fuckin bundle in no time. You bet your sweet ass. Those bucks would just be pilin up till we was ass deep in braid jim. Thats right man, and we wouldnt fuck it up like those other assholes. We wont get strung out and blow it. We/d be cool and take care of business and in no time we/d get a pound of pure and just sit back and count the bread.

Sounds promising, eh?

Meanwhile, for Harry’s mother Sara Goldfarb, the two best things in life are television and chocolate; they help plug the void left by her deceased husband Seymour. She receives a phone call one day asking if she would like to appear as a contestant on her favourite quiz show and, clutching the top of her dress, feeling her heart palpitate, can scarcely believe her luck:

Sara Goldfarb blushed and blinked, I never thought that maybe I would be on the television.

And then, soon after:

O my God, television. What will I wear???? What do I have to wear? I should be wearing a nice dress. Suppose the girdle doesn’t fit? Its so hot. Sara looked at herself then rolled her eyes back and up. Maybe I/ll sweat a little bit but I need the girdle. Maybe I should diet? I wont eat.

She heads to her closet and finds the dress, the one she will wear on television, the gorgeous red dress and gold shoes she wore when her Harry was bar mitzvahed . . . Seymour was alive then . . . and not even sick.

That was a long time ago. Now of course, the dress no longer fits. But Sara’s mind is set:

She loved the red dress. She should be able to lose the weight. She could always let the seams out a little maybe. The library will have books. Tomorrow I/ll go and get the books and go on a diet. She put another chocolate covered cream in her mouth and let the chocolate slowly melt and savoured the flavour of the chocolate mixing with the cream center then slowly squeezed the chocolate between her tongue and the roof of her mouth and smiled and half closed her eyes as her body tingled with tiny shocks2 of delight.

It's a simple premise. We understand from the outset these characters’ lives and how realising their dreams would benefit them: Harry wants a future with his girlfriend Marion, Tyron wants to escape squalor for a better life, Sara is lonely and wants to be seen; but we are suspicious of their ability to achieve what they set out. Many temptations are afoot and, as we’ve learnt from the story of Eden, they are sometimes too strong to deny.

Selby’s books are filled with trials. They seem to explore the malleability of the human spirit while under duress. The Edenic image, I believe, is a useful one, for, when I read his novels or short stories, I can’t help but picture them as modern-day bible stories.

I plan to circle back to this notion when discussing other works, but first, I want to write a little about his—

Words on the page

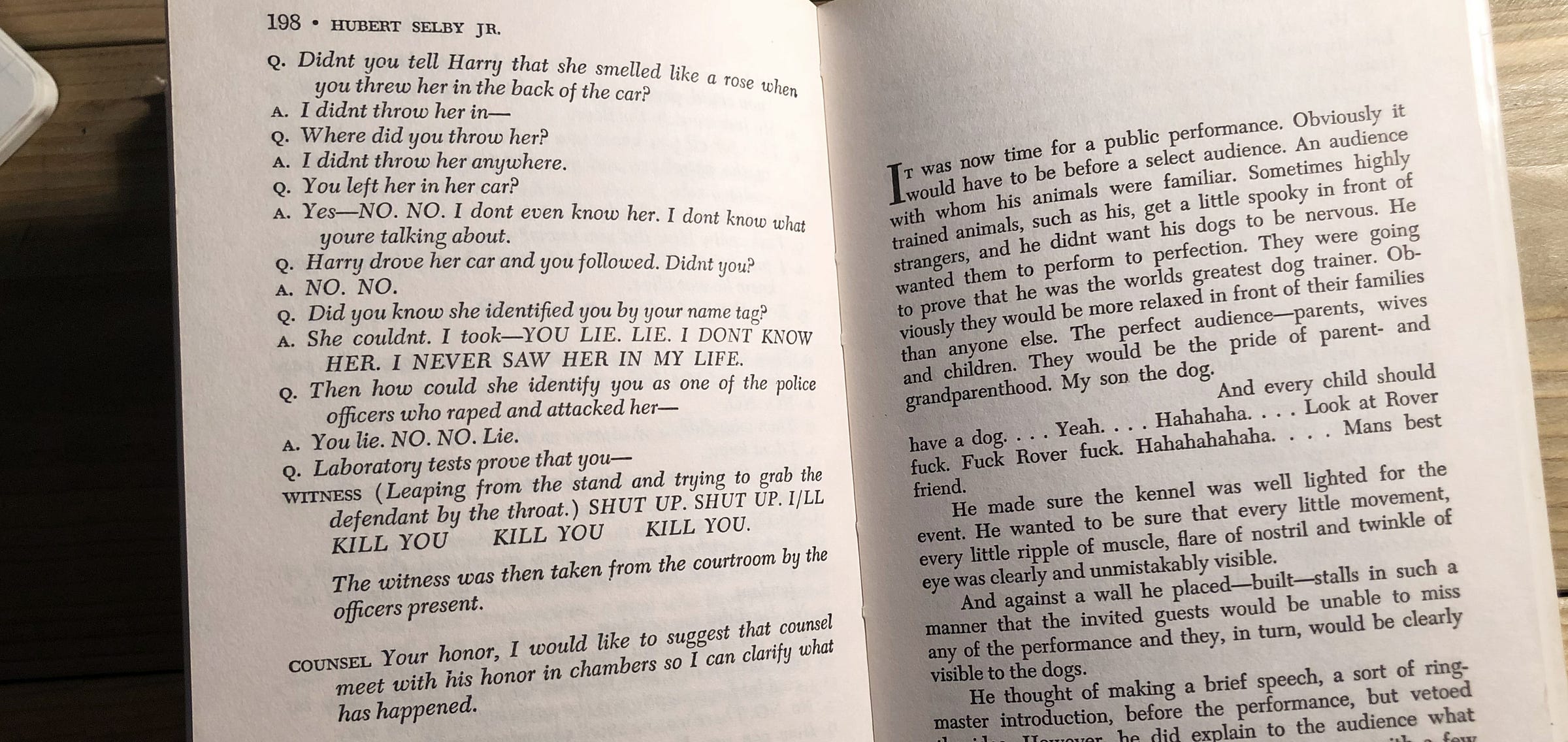

Open any Selby book to a random page and you will quickly realise this writer’s work is like no other. You may at first be struck by the total absence of apostrophes and speech marks. Then, peering closer, you find certain words like dont or wont make do without any punctuation at all, whereas others, I/ll or he/ll for example, have a slash where the apostrophe usually goes. You look elsewhere and spot a line that reads like dialogue but find no attribution to a character, nor any line breaks between interlocutors. Depending on the book, and the random page, you may see walls of text3 without paragraph breaks or see paragraph breaks that are spaced and tabbed unevenly. Were you to stop here and close the book, you’d likely be daunted from reopening it, even regretting your purchase, if it found its way to your home.

Don’t (or dont!)

Believe me, it’s not formatting peculiarities that should make you second guess your choice to read Hubert Selby Jr. (That’s what the subject matter’s for). Each of Selby’s choices to eschew literary norms were deliberate. And while the framework of conventional grammar and punctuation exists to help the writer convey a story to the reader in a way that can be easily comprehended, it is by no means law.

Selby argues that for dont or wont (or arent or isnt) punctuation is unnecessary because they are perfectly understandable without (so why include them?). However, a mark is needed for the likes of I/ll or he/ll because, without them, they become different words with different meanings. (I/ll becomes Ill, he/ll becomes hell.) As for why slashes and not apostrophes, it’s for practical reasons, economy. A slash could be delivered with a single keystroke of his typewriter4, whereas an apostrophe required holding shift with one hand to raise the hefty carriage and then striking the number 8 with the other, and when the words were flowing, this action would only slow his rhythm.

Rhythm really is the keystone of Selby’s prose; It also explains his inventive use of indents, spacing between paragraphs and lack of dialogue attribution. Although he read and was influenced by the likes of Joyce and Melville, Selby was keen to cite Beethoven as his main inspiration in how he approached writing and how he built his own ruleset.

His work is beautifully inevitable, yet never predictable, no matter how many times you hear it.

Alike a musical score, fiction is predominantly5 linear. We proceed from page one line one onwards. However, music prescribes pacing with time signatures and Beats Per Minute. Notes have additional meaning, also. There is a note's pitch (where it appears on the five-lined stave) but also its length: whole note, half-note, quarter-note and so on. To achieve a similar effect in his writing, Selby’s solution was to vary the spacing between paragraphs and even words within sentences. Assuming you read at a steady clip, longer breaks are employed when Selby wants the previous sentiment to linger, while shorter ones are to get you trucking onto the next line.

Rhythm also factors into his dialogue. Selby would assign unique speech patterns (and pronunciation) to each character. For instance, some speak in short staccato sentences and might drop the g from words like foolin or breakin, while others are articulate, enunciate every letter and even alliterate.

He would apply further “eye dialect” tricks, such as spelling words different ways to convey accents. Selby was also a frequent user of full caps, for he does not write, '—shouted Harry', Harry simply SHOUTS, and also of Joycean portmanteaus like sonofabitch or screwem, which, when you think about it, seems the more sensible spelling for how they roll off the tongue in a single unbroken glissando. It's with these distinctions that Selby charts the change of speaker.

Selby’s syntactical decisions were not only sound but married perfectly with what he elected to write.

‘Harry’ crops up a bunch in Selby’s work. In Last Exit to Brooklyn it’s Harry Black, in The Demon Harry White, in Requiem for a Dream Harry Goldfarb, in Fear X Harry Caine.

Wonderful foreshadowing.

If you happened to open Last Exit to Brooklyn, near the end, you may find those text walls bricked up in full-caps.

A portable Remington.

I say predominantly because books like Nabokov’s Pale Fire, or ones containing footnotes encourage disrupting that innate linearity.